1. Segmental vs. parametric views of speech

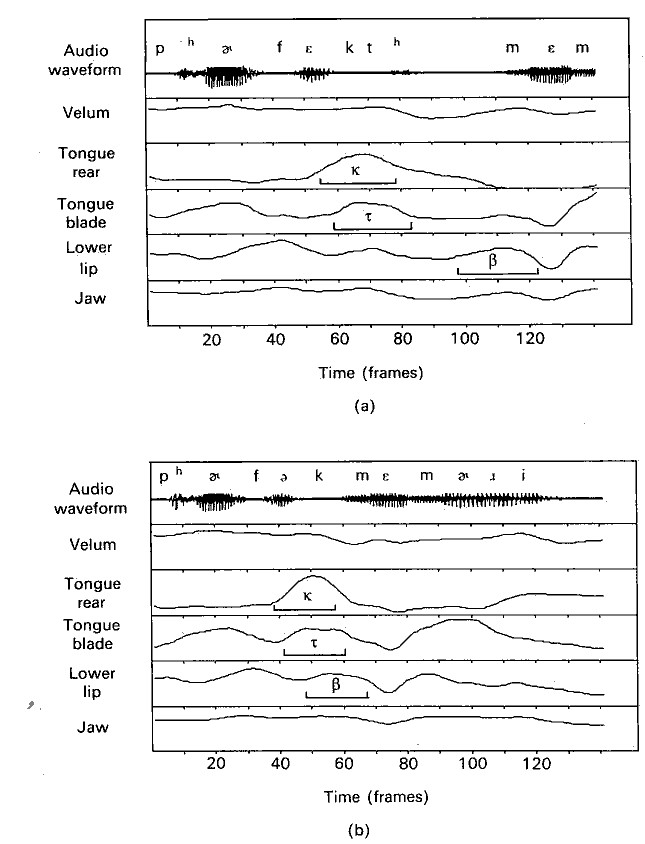

In studying the IPA alphabet, we may become so focussed on the linear sequence of consonants and vowels that we forget the fundamental fact that speech is produced by six independently-controlled organs (lungs, larynx, jaw, velum, tongue and lips) all moving simultaneously and continuously.

2. Pitch, tone and intonation

Pitch

refers to the perception of relative frequency (e.g. perceptually

high-pitched or low-pitched) of the vibrating vocal cords.

Intonation refers to the rise and fall of voice pitch over entire phrases and sentences, as in English:

3.

Terminology.

For this reason, intonation is sometimes called a supra-segmental

feature. This

terminology implies that phonetic and phonological features can be

separated into two subsets: segmental and suprasegmental features.

This

is not really correct, as we shall soon see. For this reason, I

prefer

to avoid the term "suprasegmental". Instead, I shall talk about the

prosodic function of

features.

Almost any feature can be used prosodically or segmentally,

depending

on the language.

In English, we also use pitch (in

conjunction with other features) to distinguish a few pairs of

words;

e.g. DEfect (n.) vs. deFECT.

It is quite common for pitch and

stress to be closely related. In some languages, in fact, pitch

seems

to play a role that is rather like stress in English: these are

often

referred to as pitch-accent

languages. E.g. Croatian:

| Long rising | Short falling | |||||||

| ʋǐːle | vile | ʻfairiesʼ | ʋîle | vile | ʻhayforkʼ | |||

| dǔːɡa | duga | ʻrainbowʼ | dûga | duga | ʻstaveʼ | |||

Tone refers to significant (i.e.

meaningful,

constrastive, phonemic) constrasts between words signalled by pitch

differences.

Tone may be lexical, as

in Mandarin Chinese:

Or grammatical

tone, as in many African languages, e.g.

Edo:

| Tense | Monosyllabic verbs | Disyllabic verbs |

| Timeless | [ì mà] ʻI showʼ | [ì hrùlè] ʻI runʼ |

| Continuous | [í mà] ʻI am showingʼ | [í hrùlé] ʻI am runningʼ |

| Past | [ì má] ʻI showedʼ | [ì hrúlè] ʻI ranʼ |

However, there may also be non-pitch aspects of tone. Lexical tones are often related to durational, phonatory and vowel quality distinctions as well as frequency distinctions. For example, Mandarin Chinese tone 3 (low rise) is long with creaky voice, Hunanese tone 2 has breathy or chesty voice. Tibetan tone 1 words have voiceless initial consonants whereas tone 2 words have voiced beginnings. Long vowels in tone 4 or 5 open syllables in Thai are checked by a final glottal stop.

All of these variations in pitch require the tension of the vocal cords to be adjusted up and down at the same time as the other articulators are moving, as in Browman and Goldstein's diagram in section 1 above.4. What else can be a prosody?

Virtually anything!

4.1.

Laryngeal features

In addition to tone and intonation, several other laryngeal features are prosodic in some languages. In Cœur d'Alène, a dying Salishan language spoken in northern Idaho by few speakers ("less than a handful" in 1966), glottalization (probably creaky voice, glottal stops and glottalic consonants) is used as a diminutive morpheme:

| mar-marím-EntEm-ilts | vs. | m̰-m̰ar̰-m̰ar̰ím-En̰tem̰-il̰ts |

| \___________________/ | \__________________________/ | |

| not glottalized | glottalized | |

| ʻthey were treated one by oneʼ | ʻthey little ones were treated one by oneʼ |

A complex of creaky voice, pitch and

loudness in Danish (stød)

distinguishes words in a way that parallels the use of contrastive

tones in Swedish or Norwegian, e.g. [bœn] ʻbeansʼ vs. [bœnʔ],

or [thɒŋgn̩] ʻthe thoughtʼ vs. [thɒŋʔgn̩].

(See Laver 1994 and Grønnum 1998 for further examples.) Although

I have transcribed these

using a glottal stop symbol, the glottalization is more dispersed, and

may involve creaky voiced vowel, creaky voiced sonorant consonants,

falling pitch, and glottal closure. It is therefore usually analysed

as

a prosodic feature, rather than a segmental feature.

Fischer-Jørgensen (1987) is a very thorough study (part of it

conducted here in the Oxford Phonetics Laboratory in 1981! A copy is

in the lab library.)

Voicing assimilation is another

(perhaps less spectacular) example of a feature not staying nicely

confined within a segment. For example, in Russian,

there is a maximum of

1 voicing distinction in consonant clusters. A cluster takes on the

voicing of the last consonant in the sequence, without regard to

boundaries:

| Morphemic boundary: | /gorod+k+a/ | |

[gorotka] | ʻlittle townʼ |

| Clitic boundary: | /mtsensk# bi/ | |

[mtsenzgbɨ] | ʻif Mcenskʼ |

| Word boundary: | /mtsensk## bil/ | |

[mtsenzgbɨl] | ʻit was Mcenskʼ |

Sonorants e.g. [m] are not

distinctively voiced, and they are transparent

to voicing assimilation:

| iz # mtsensk+a | |

[is mtsenska] | ʻfrom Mcenskʼ |

| ot # mzd+i | [od mzdɨ] | ʻfrom the bribeʼ |

Some French examples:

| anticipation of [+voice]: | |

anticipation of [-voice]: |

|

je passe vite [paz vit]

|

chemin de fer [t fɛːʁ]

|

|

|

la tête droit [tɛd dʁwat]

|

coup de pied [ku t pje]

|

|

|

avec vous [avɛg vu]

|

esprit de corps [ɛspʁi

t kɔːʁ]

|

|

|

place d'armes [plaz daʁm]

|

tout de suite [tu t sɥit]

|

|

|

rez-de-chaussée [ʁe

t ʃose]

|

4.2. Velum movement

| 3rd person possessives (non-nasal) |

1st person possessives (nasal) |

|

| eˈmoʔu ʻhis wordʼ | ẽˈmõʔũ ʻmy wordʼ | |

| ˈajo ʻhis brotherʼ | ˈãj̃õ ʻmy brotherʼ | |

| ˈowoku ʻhis houseʼ | ˈõw̃õŋgu ʻmy houseʼ |

Sundanese

(Austronesian, W. Java) (Robins 1957):

ɲaian [ɲãĩãn],

ʻto wetʼ

miasih [mĩʔãsih], ʻto loveʼ

kumaha [kumãhã], ʻhow?ʼ

4.3.

Tongue root prosodies

4.3.1.

Spread

of velo-pharyngealization in

Tashlhiyt Berber.

This language

(like various other Afroasiatic languages, such as Arabic)

has a

contrast between pharyngealized

and non-pharyngealized coronal consonants, as well as some

pharyngeal

consonants. In words containing these consonants, entire

syllables or

even the whole word becomes pharyngealized, as you can hear

from these

audio clips:

4.3.2. [ATR] harmony

In a number of languages of West

Africa, a particular pattern of vowel harmony is found in which the

vowels fall into two sets: more advanced and higher vowels {i, e, o,

u}

and correspondingly less advanced and lower {ɪ, ɛ, ɔ, ʊ}.

[a] is

typically "neutral", and can co-occur in words with vowels of either

set. In the more advanced and higher vowels, the tongue root has been

found to be more advanced, and hence they are given the feature

[+Advanced Tongue Root] or [+ATR]: the non-advanced vowels are

consequently labelled [-ATR]. See Laver (1994: 289-291) and references

therein, and Tiede (1996) for MRI images of Akan [i] vs. [I].

The

vowel system of Ega (Kwa, Côte d'Ivoire) (Connell,

Ahoua and Gibbon 2002) is quite typical:

| High, [+ATR] |

i | u |

||||

| High, [-ATR] | I | ʊ | ||||

| Mid, [+ATR] | e | o |

||||

| Mid, [-ATR] | ɛ | ɔ | ||||

| Low |

a |

Examples of words containing vowels in

the two sets (note that Ega also

has tones, not transcribed here):

| [+ATR] |

[-ATR] |

|||||

| |

efi |

ʻeyeʼ | ɔvɛ | ʻsilk cotton treeʼ | ||

| oji |

ʻcoldʼ |  vɛ vɛ |

ʻdogʼ | |||

| efe |

ʻtaking flightʼ | ɛɲɛ | ʻarrivalʼ | |||

| uje |

ʻbundle of woodʼ | ɔsI | ʻwomanʼ | |||

| emo |

ʻsmellingʼ | ɛzɔ | ʻquarrelʼ | |||

| ize |

ʻwoodʼ | ɛcI | ʻlaughingʼ |

4.4. Tongue body prosodies; lip prosodies

Vowel harmony systems involving

frontness vs. backness, openness vs. closeness or lip-rounding vs.

lip-spreading are widely documented in the phonetics and phonological

literature, and exemplify the prosodic use of tongue body and lips.

4.5.

Tongue tip prosodies

Finally, a number of languages have

harmony systems involving tongue-tip consonants: all the coronal

consonants of a word are either more advanced. [+anterior], or less

advanced, [-anterior]. In some languages this distinction is dental

vs.

alveolar, in others alveolar vs. post-alveolar. In Coleman (2003), I

present evidence that English also exhibits this kind of [anterior]

harmony to some extent. For example:

| Chumash (Chumashan, California

(extinct)) |

k-sunon-us |

ʻI obey himʼ |

| k-ʃunon-ʃ | ʻI am obedientʼ | |

| Tahltan (Athabaskan, NW Canada) |

ɛsdɑn |

ʻI'm drinkingʼ |

| dɛθkwʊθ | ʻI coughʼ | |

| Zayse (Omotic, Ethiopia) |

zatst |

ʻleadʼ |

| ʔiʃitʃ | ʻfiveʼ | |

| English |

ʌthəsɑɪ |

ʻutter sighʼ |

| ʌthəʃɑɪ |

ʻutter shyʼ |

4.6. Manner of articulation (degree of stricture)

5. Prosody reconsidered

The preceding examples have shown that many more features than duration and pitch are (or can be) prosodic. What, then, do we mean by ʻprosodyʼ if not just tone, stress, intonation, and loudness, the traditional ʻsuprasegmentalʼ features?

a) Features (or groups of features) that not located at a single place in the sequence of consonants and vowels.

b) For example, (groups of) features associated with a whole syllable, word or phrase.

c) Also, features of the boundaries

of syllables and words

(e.g. assimilation, liaison, absence vs. presence of sounds in

particular syllable or word positions). ʻGrenzsignaleʼ

(Trubetzkoy 1969: 273-297). Recognition of the non-segmental behaviour

of features, and the close relationship between features and the

specific places in syllable or word position in which they occur, led

to the origin in the mid 1930ʼs to the London school of "prosodic

phonology", under J. R. Firth, which presented a thorough critique of

and offered a theoretical alternative to phonemic phonology. Some of

the ideas of the prosodic school have influenced the contemporary

mainstream of phonological theory, especially via the framework of

Autosegmental Phonology.

Bendor-Samuel, John T. (1960) Some problems of segmentation in the phonological analysis of Tereno. Word 16, 348-355.

Coleman, John (2003) Discovering the acoustic correlates of phonological contrasts. Journal of Phonetics 31, 351-372.

Connell, Bruce, Firmin Ahoua and Dafydd

Gibbon (2002) Ega. Journal of the

International Phonetic

Association 32, 99-104.

Fischer-Jørgensen, Eli (1987) A phonetic study of the stød in Standard Danish. Annual Report of the Institute of Phonetics, University of Copenhagen vol. 21. 55-265.

Grønnum, Nina (1998) Danish. Journal

of the International Phonetic

Association 29, 99-105.

Laver, John (1994) Principles

of

Phonetics. Cambridge University Press.

Robins, Robert H. (1957)

Vowel nasality in Sundanese: a

phonological and grammatical study. Studies

in

Linguistic Analysis. The Philological Society. 87-103.

Tiede, Mark (1996) An MRI-based study of pharyngeal volume contrasts in Akan and English. Journal of Phonetics 24, 399-421.

Trubetzkoy, N. S. (1969) Principles

of Phonology. (English

translation of Grundzüge der

Phonologie.) University of California Press.